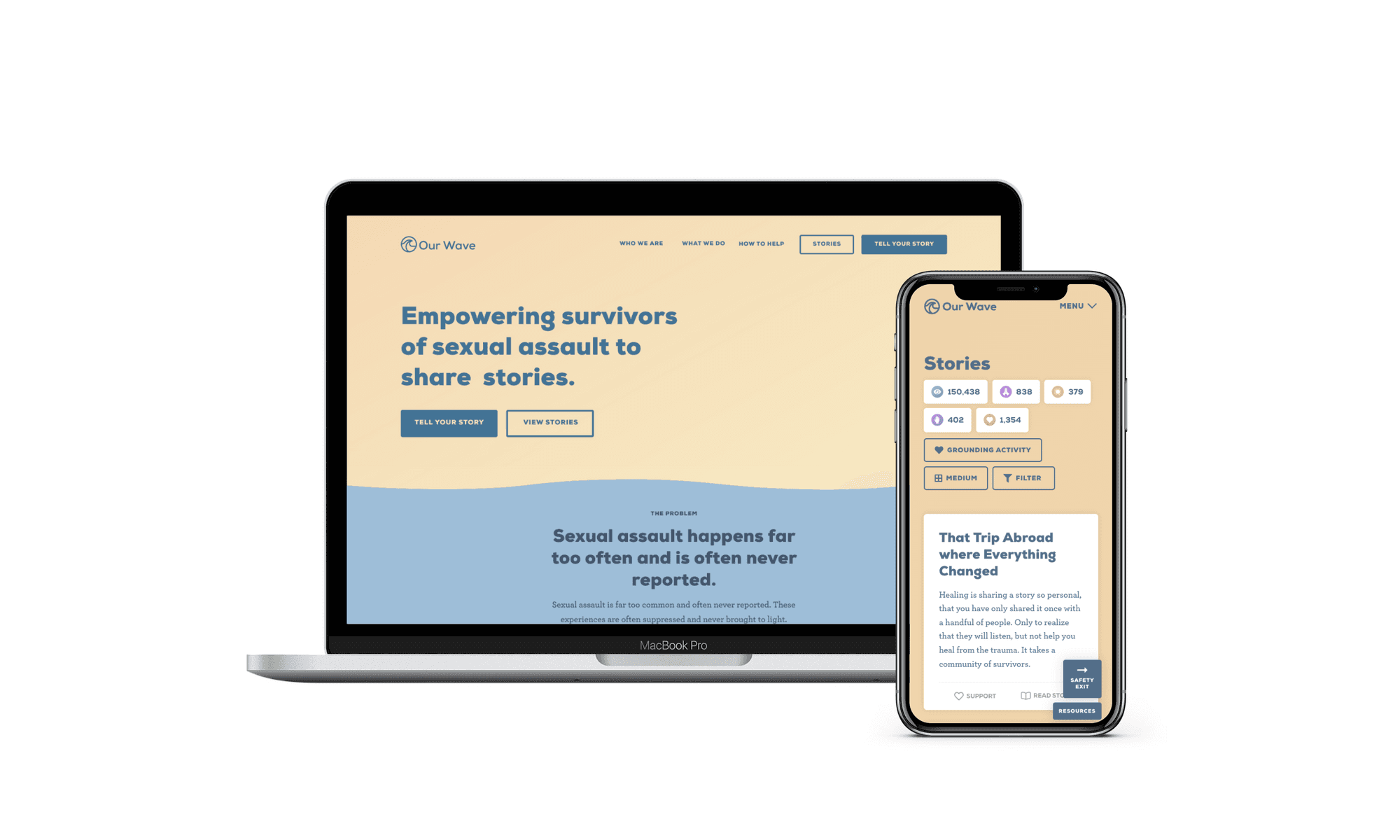

Our Wave

Designing for safety, anonymity, and hope

Org: Our Wave (nonprofit)

Role: Director of UX Research

Location: Raleigh, NC

Duration: 2 years (2018-2020)

Prototype demo: Our Wave 2020

Survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence often don’t have a safe, anonymous space to share their stories and find support. Our Wave set out to create an online platform where they can tell their stories anonymously, read others’ experiences, and feel believed and less alone.

I led UX research and design to define what a safe digital space looks like, then turned those insights into core flows and an evidence-based visual identity. The result is a calm, supportive platform where survivors can share on their own terms.

Our Wave now has over 460,000 community members and has helped refer over 110,000 people to support resources in times of need.

Context

Survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence often lack a safe, anonymous space to share their stories, connect with others, and access support. Our Wave set out to build an online platform where survivors could:

Share their stories anonymously

Read and respond to others’ experiences

Feel believed, supported, and less alone

The founding team had strong intuition this was needed, but we wanted to ground the product in evidence, survivor voices, and trauma-informed design.

My role was to lead UX research and help shape the product strategy, visual identity, and core experience from concept through launch.

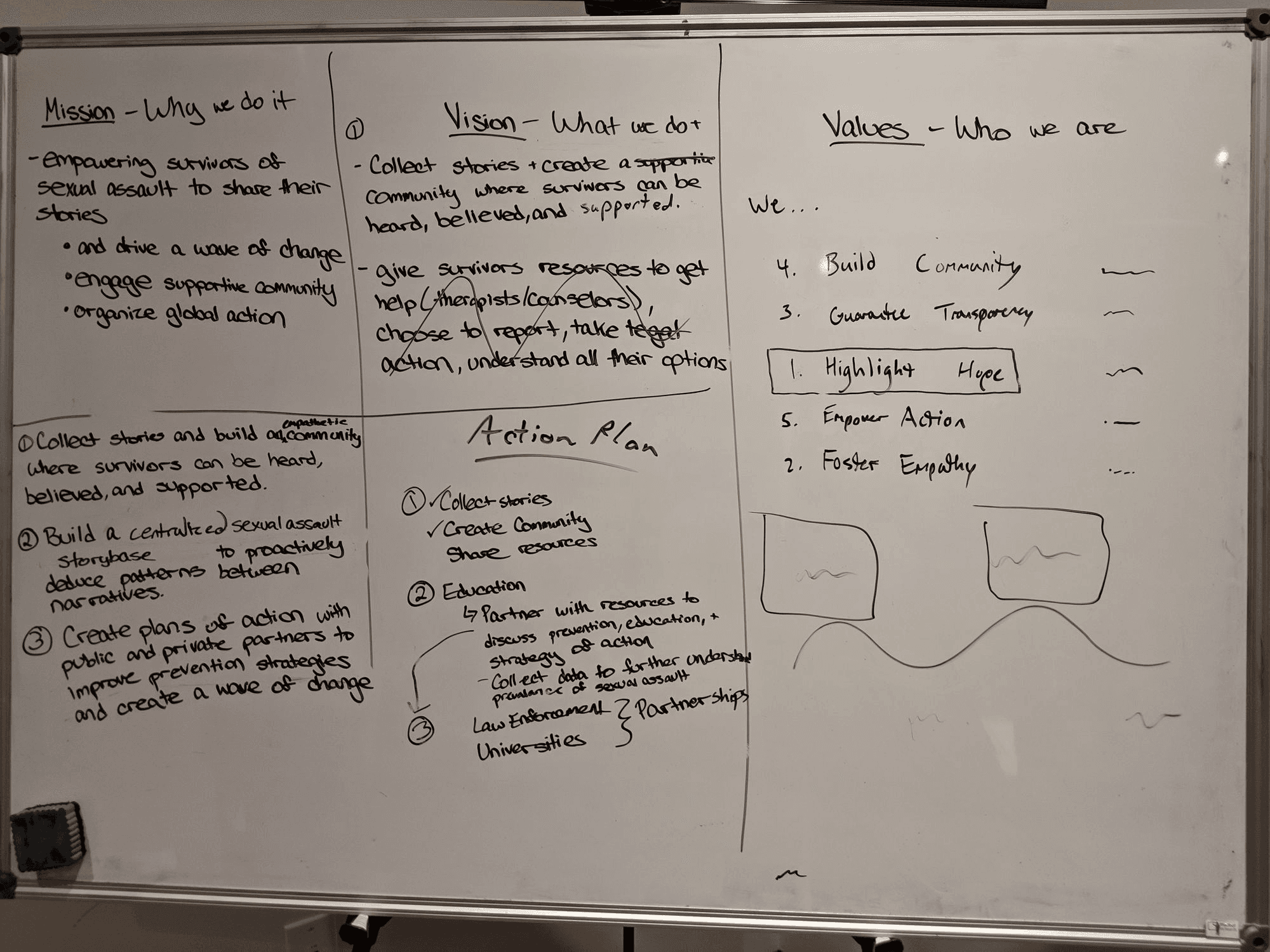

Defining our Values, Vision, and Mission

Values - Who we are

We...

Highlight Hope

Foster Empathy

Guarantee Transparency

Build Community

Empower Action

Vision - What we do

Collect stories and build an empathetic community where survivors can be heard, believed, and supported

Build a centralized story base to proactively deduce patterns between narratives

Create plans of action with public and private partners to improve prevention strategies and create a wave of change

Mission - Why we do it

We help survivors find hope and connection on the path to healing:

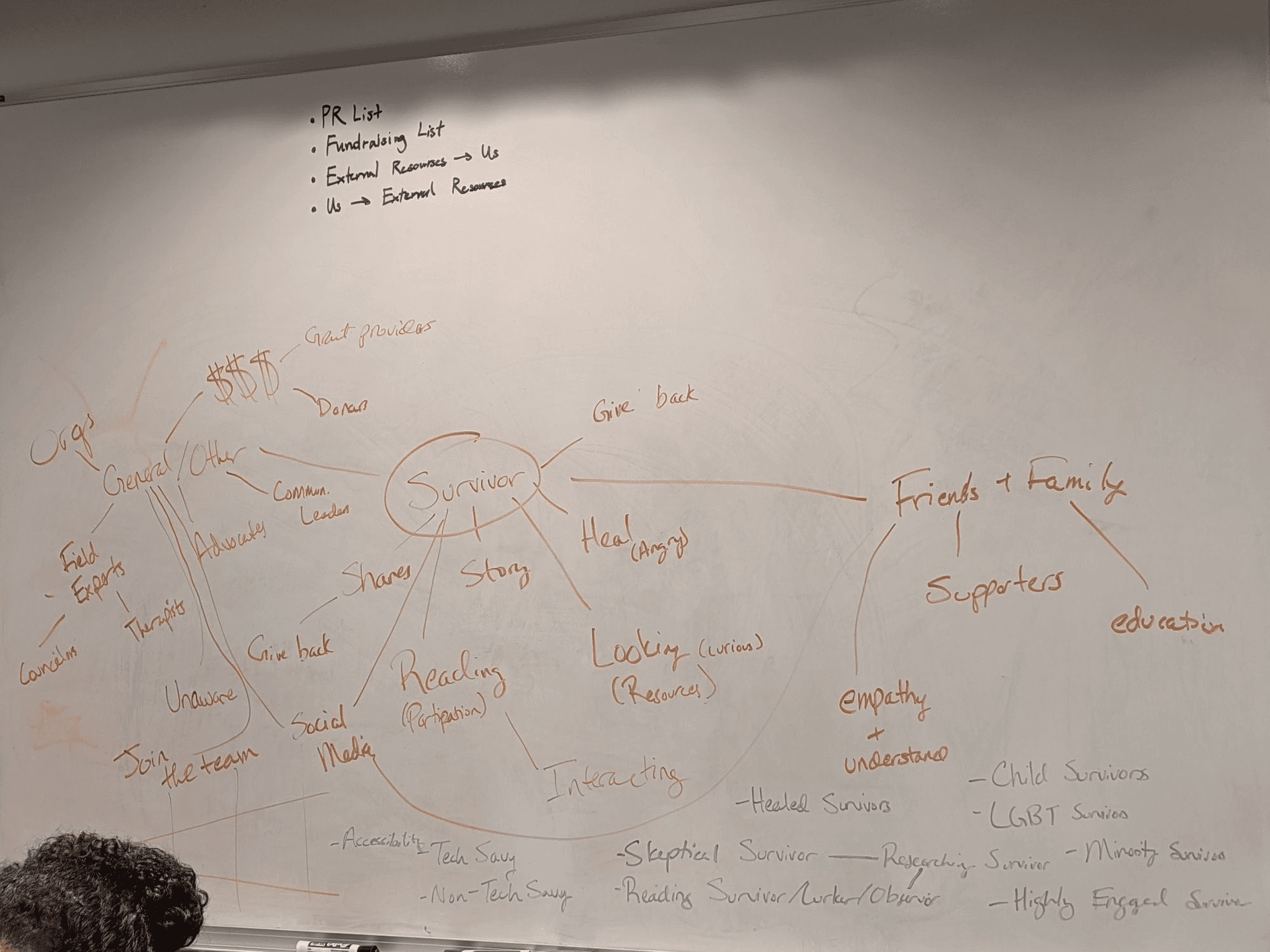

Understanding the Needs of Survivors

Reviewing the science on healing and social support

I started with a review of clinical and psychological research on trauma recovery and social support. Across multiple studies, a consistent pattern showed up:

Supportive, empathetic social connections and opportunities to process the trauma are linked to better long-term outcomes.

Avoidance, suppression, and isolation tend to increase distress.

Social support is thought to facilitate positive change because supportive others give individuals the opportunity to talk about and cognitively process the trauma.¹ […] Social support is associated with more effective coping, which in turn is associated with reporting more positive change.²

Engaging with others, cognitive restructuring, and expressing emotions facilitate recovery. Avoidance-oriented coping strategies, however, hinder recovery. Individuals who engage in social withdrawal or who repress or deny thoughts and feelings about sexual violence experience greater distress.³ ⁴ ⁵

This reinforced that Our Wave needed to:

Make it emotionally safer to talk about trauma

Encourage gentle, voluntary storytelling and connection

Avoid anything that might feel exposing, shaming, or out of the survivor’s control

These insights became guiding principles for both product and content decisions.

Partnering with trauma experts

Because of the topic’s sensitivity, we worked closely with:

Clinical trauma specialists

Survivor advocates and support organizations

They helped us:

Review our research instruments for safety and tone

Identify potential triggers in language and UI

Define red lines around anonymity, data handling, and crisis escalation

Their feedback influenced everything from our survey wording to button labels.

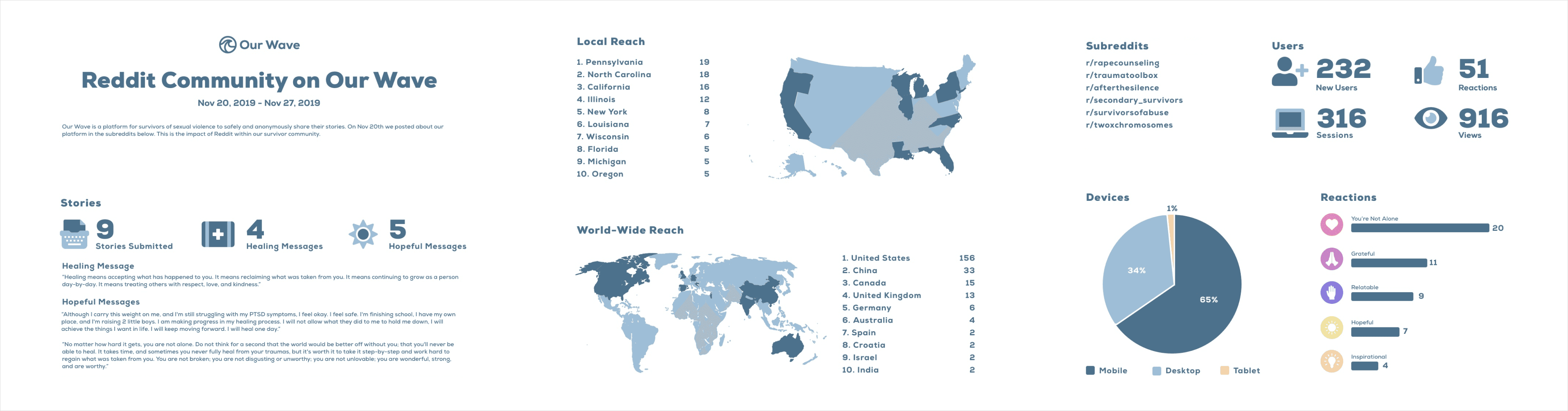

Anonymous surveys and community outreach

To validate the need and better understand potential users, we ran two rounds of anonymous surveys in online communities (including Reddit survivor and support forums). Our goals were to:

Validate the need for a safe, anonymous storytelling platform

Understand post-trauma behaviors and coping strategies

Learn about willingness to share stories and current platforms used

Learn about demographics and self-identified social groups

We:

Iterated the survey through several rounds with clinicians and advocates

Reduced it to 11 tactful, non-invasive questions

Explicitly emphasized anonymity and voluntary participation

Across both rounds, we collected over 230 responses from survivors with varied backgrounds and identities. While we don’t share raw data to protect anonymity, the key signals were clear:

Many survivors had never shared their story publicly but wanted to

Existing platforms often felt unsafe, judgmental, or too identifying

People wanted to feel believed, in control of what they shared, and connected to others with similar experiences

This gave us strong justification to move forward and concrete themes to design for.

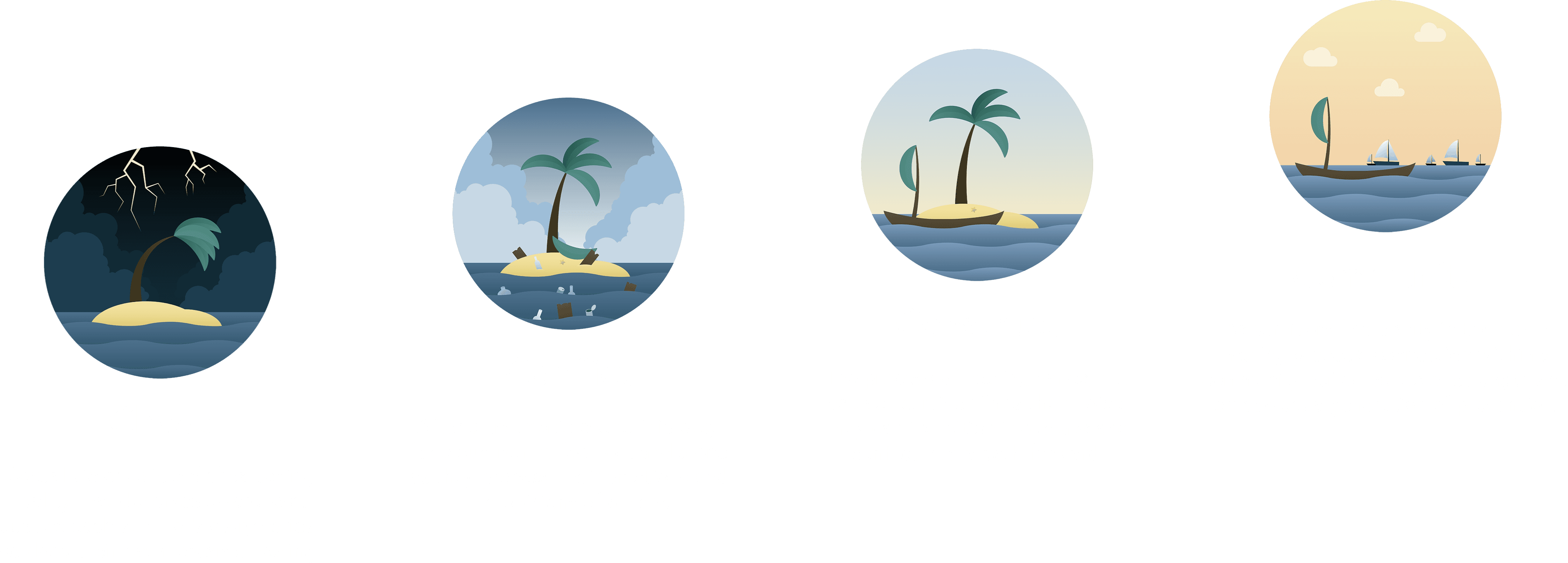

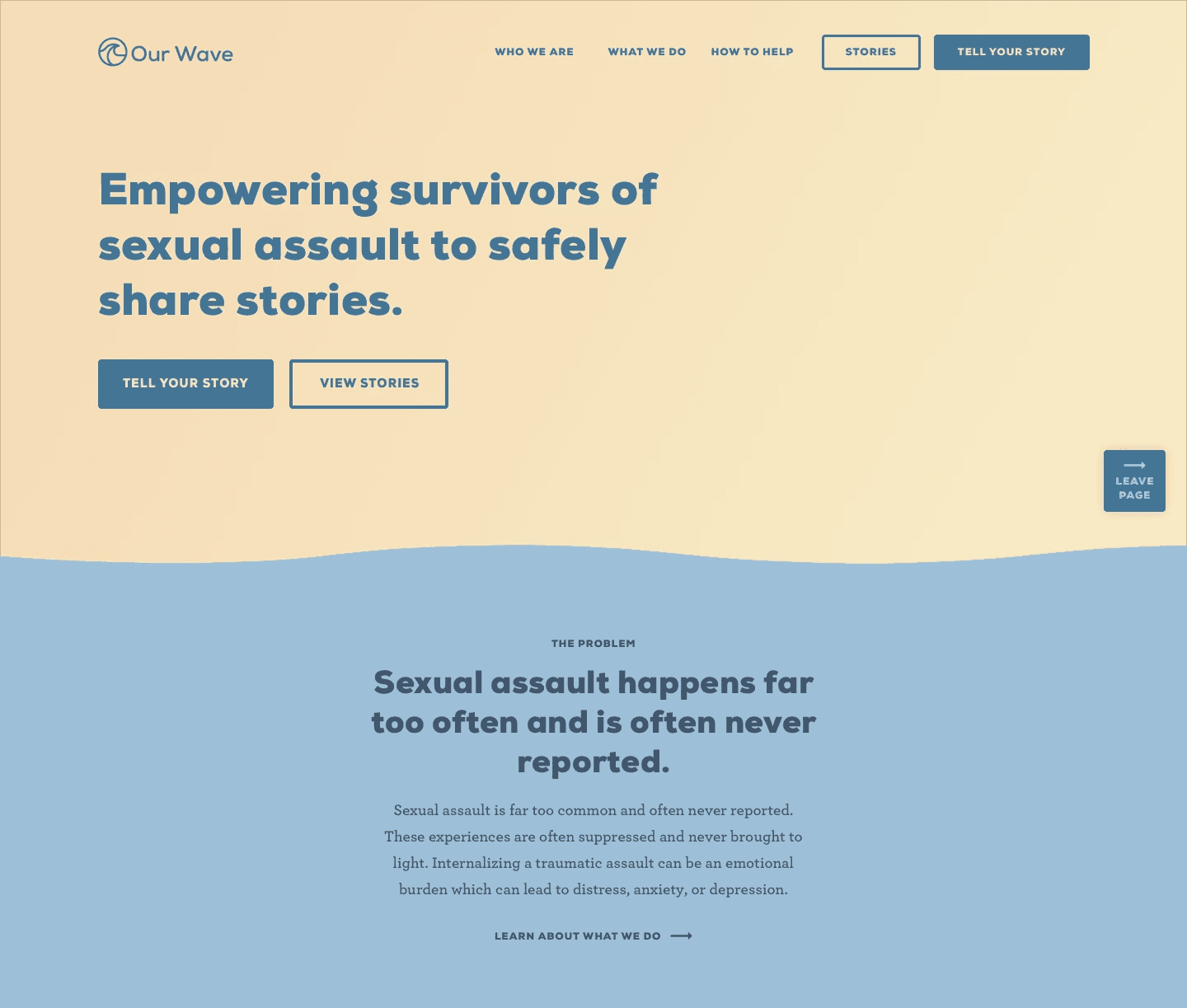

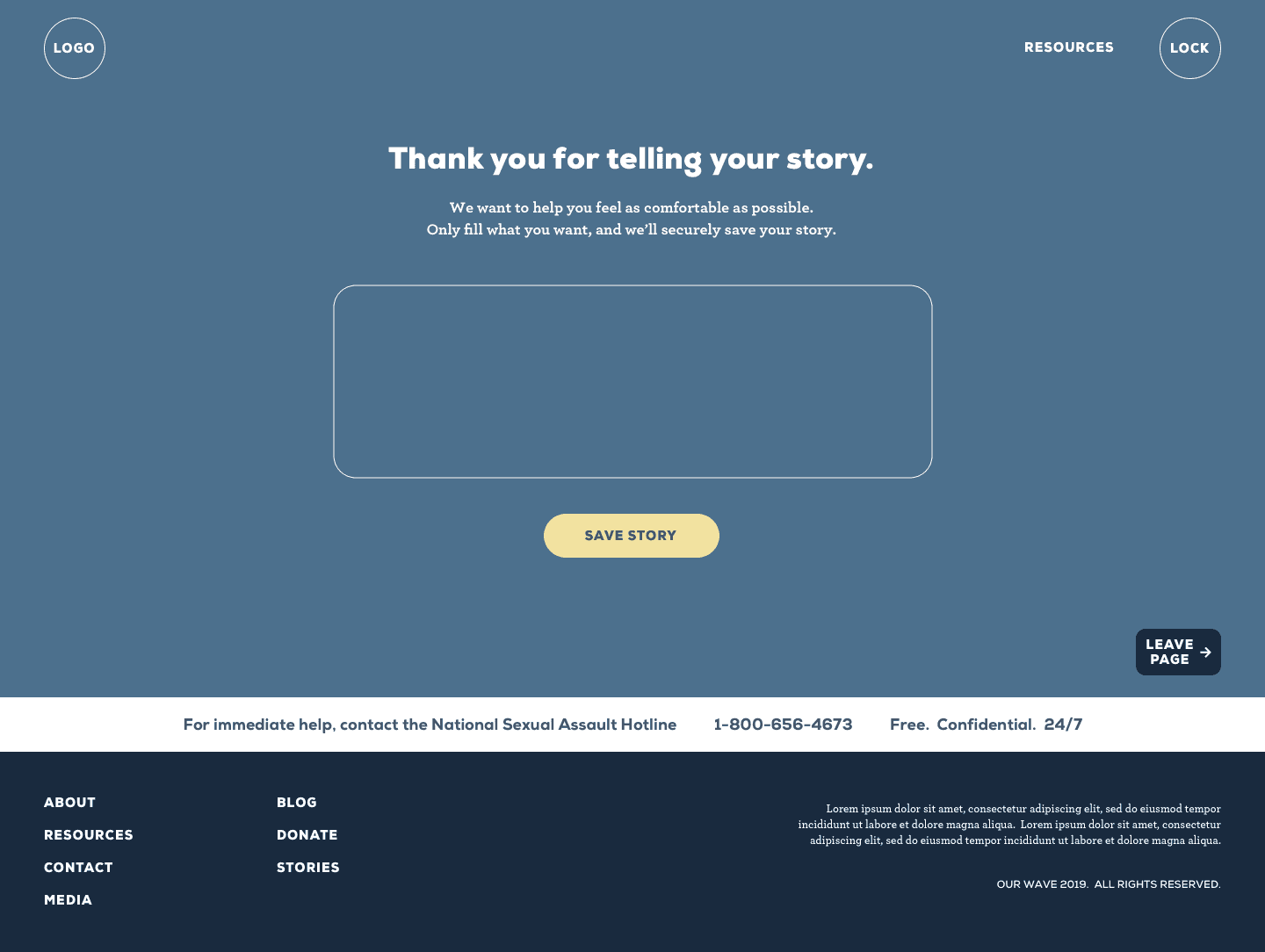

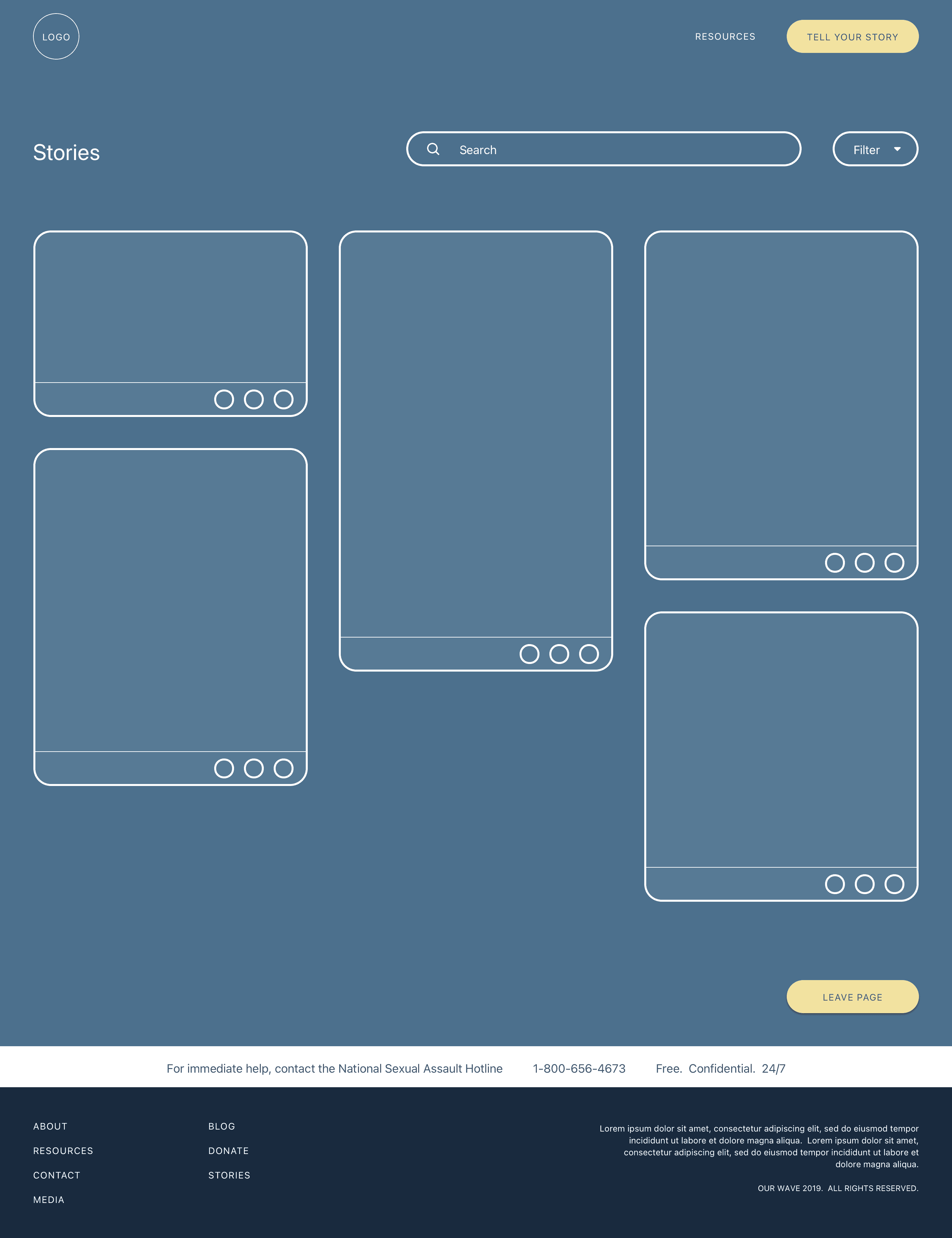

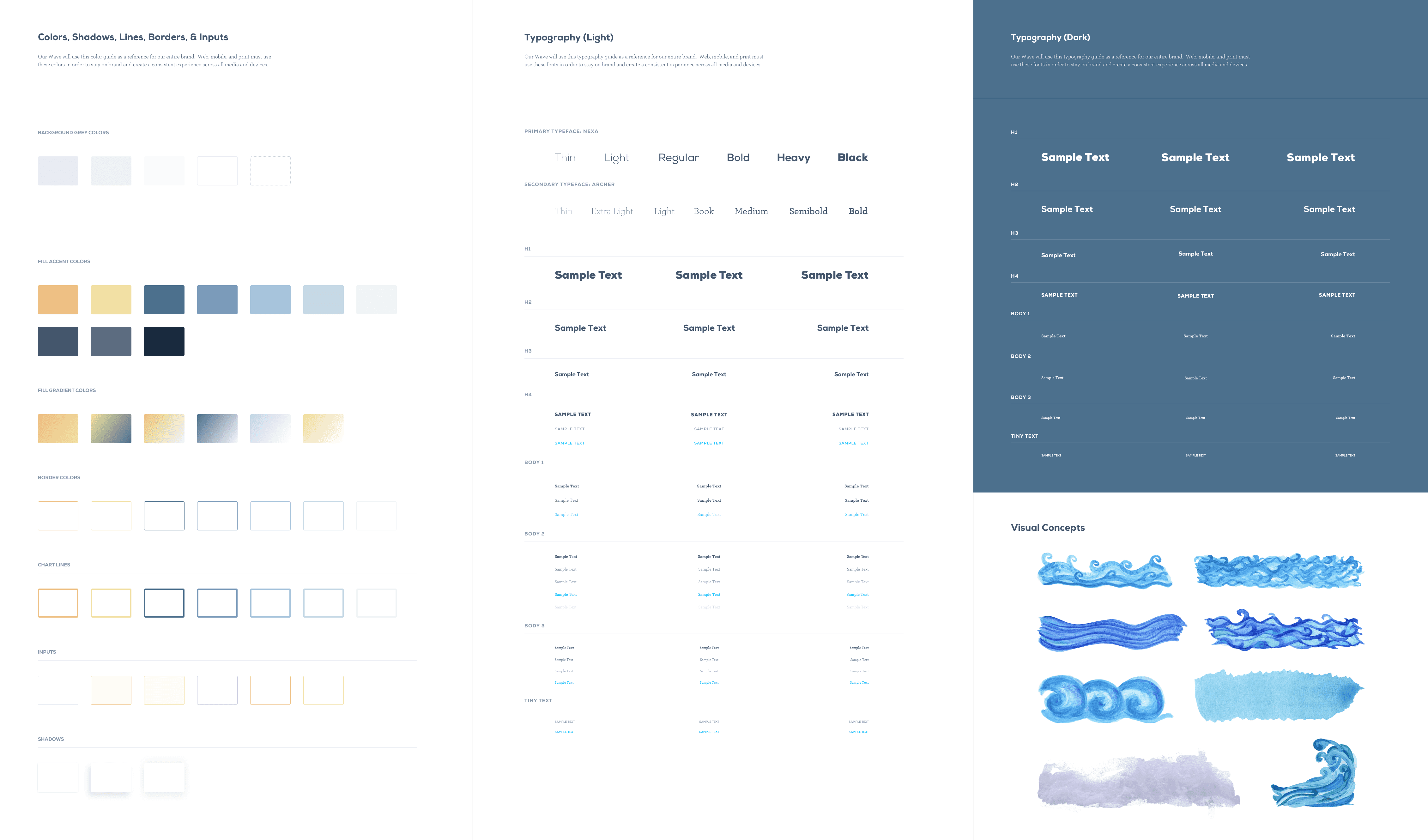

Visual Identity

The visual system needed to feel calm and hopeful.

Soft blues and warm neutrals inspired by waves/sunrise.

Simple layouts, generous whitespace, clear type hierarchy.

Accessible contrast and typography tuned for reading comfort.

No graphic or sensational imagery.

The result felt more like a quiet, reassuring space than a typical news or social app.

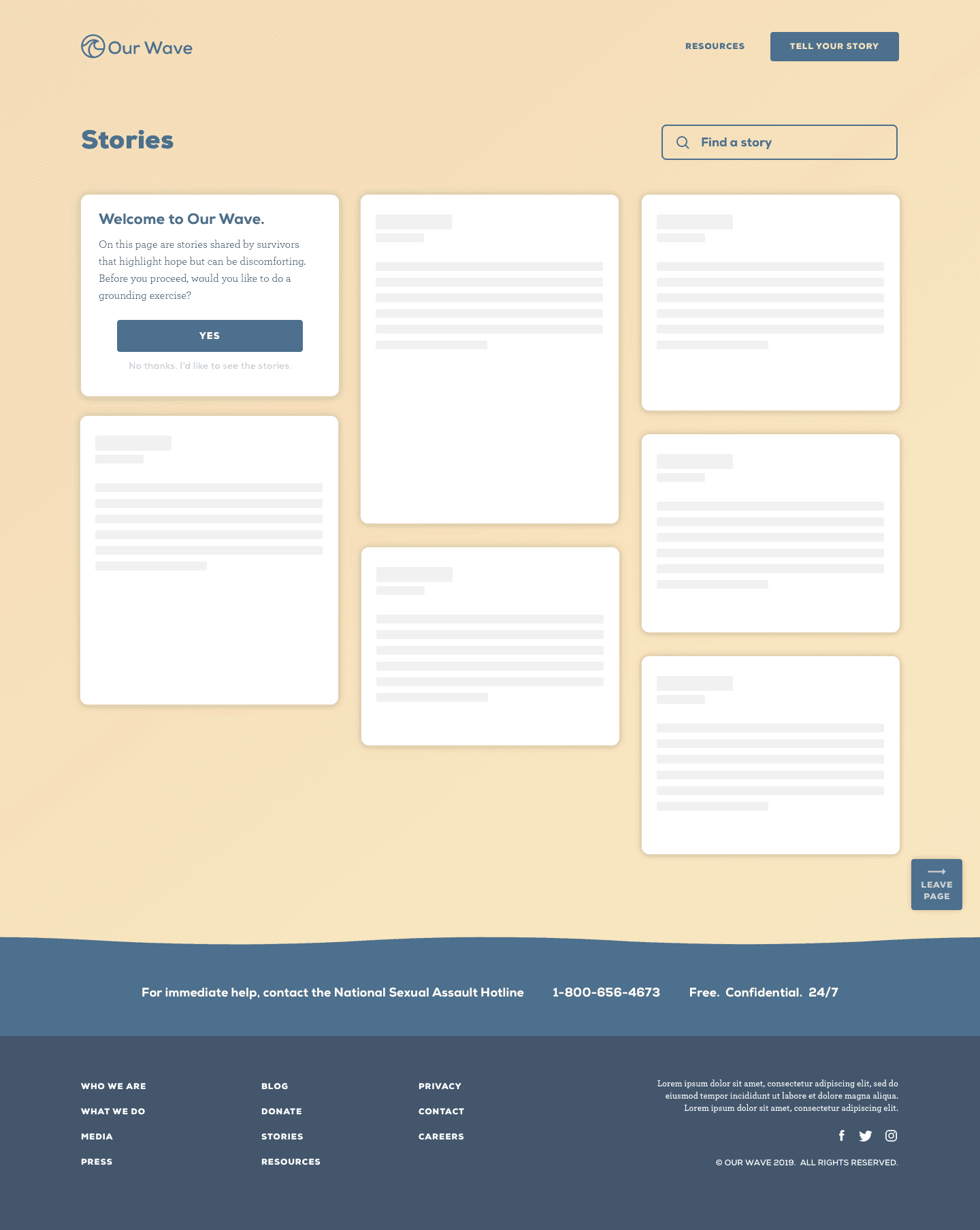

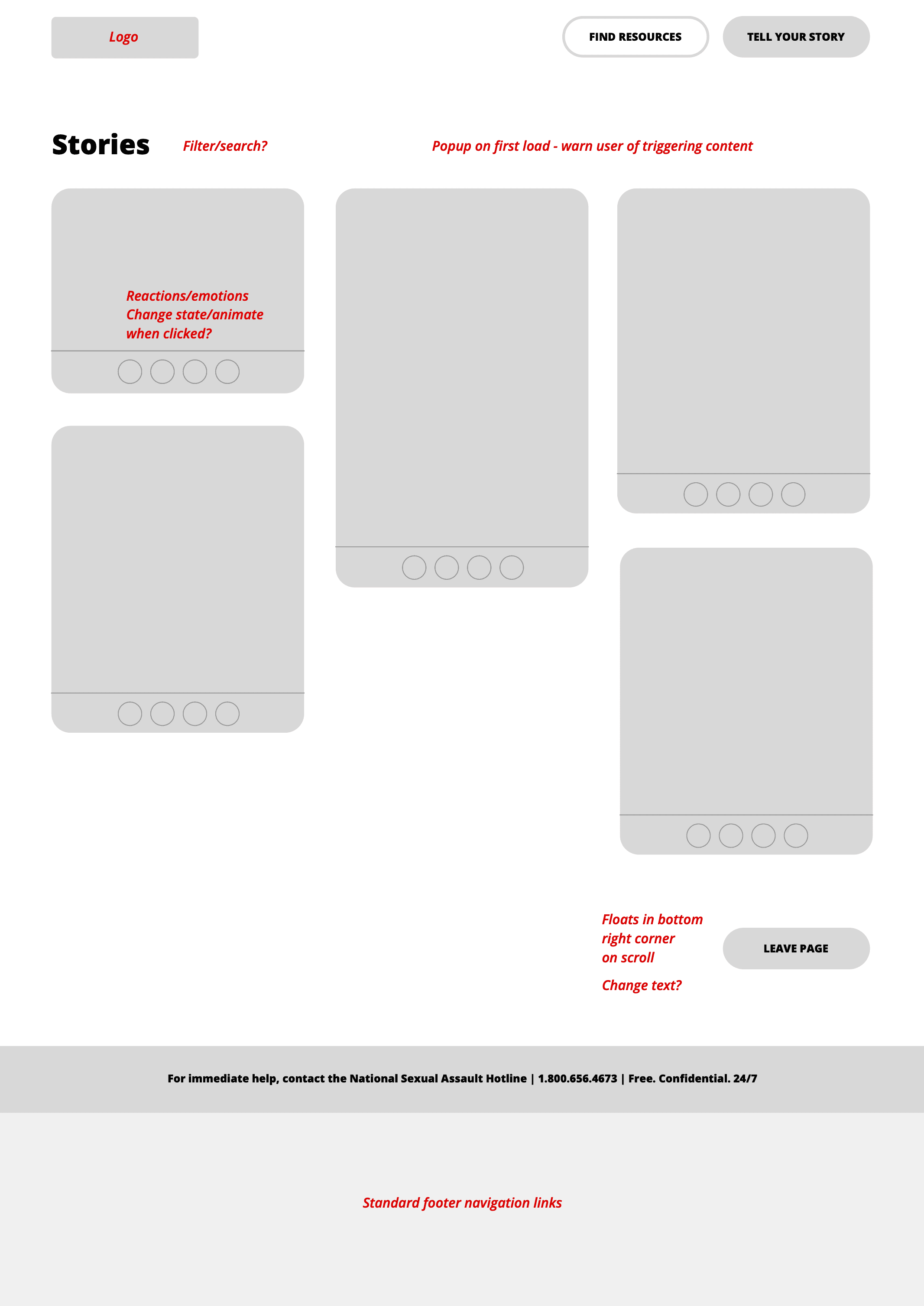

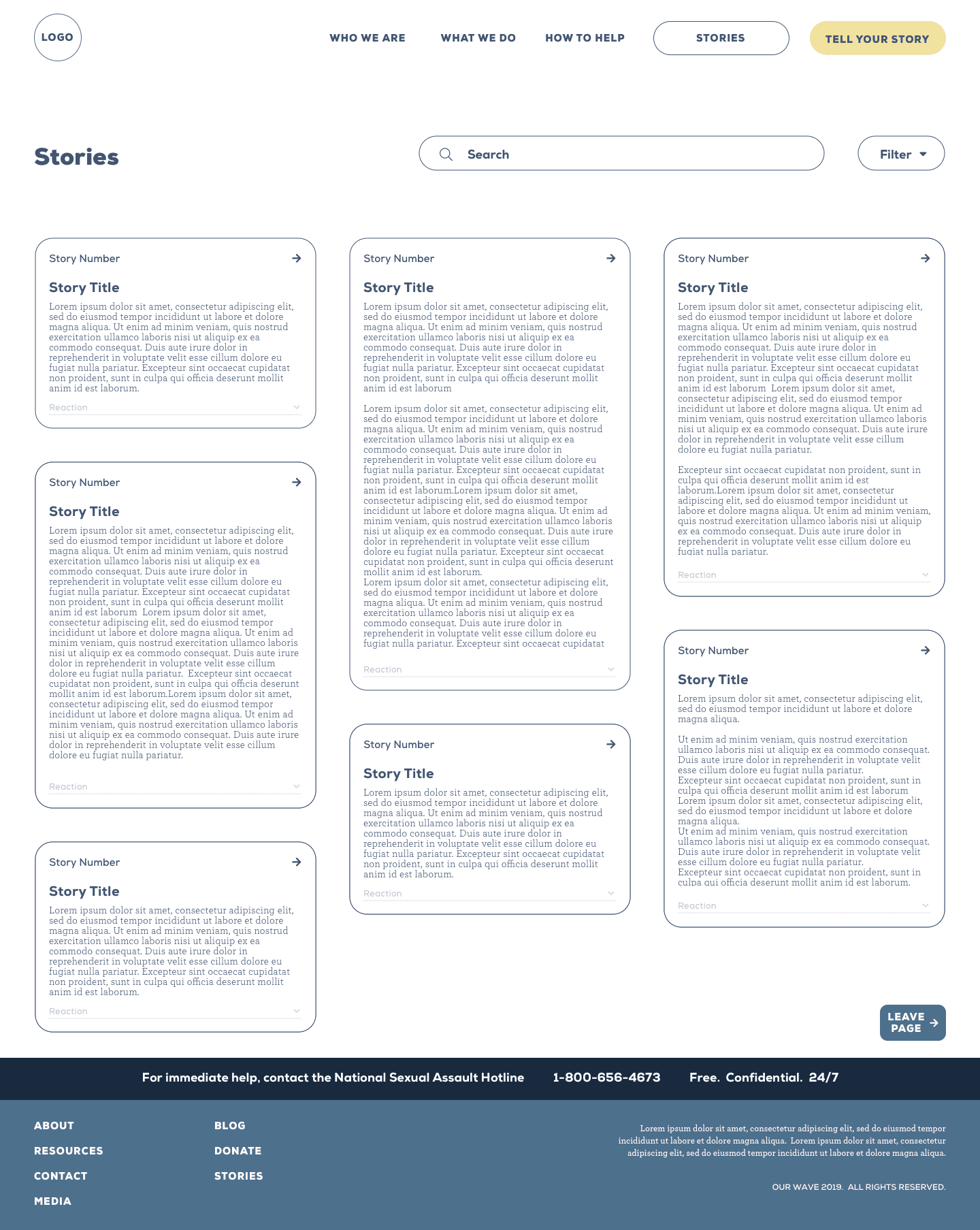

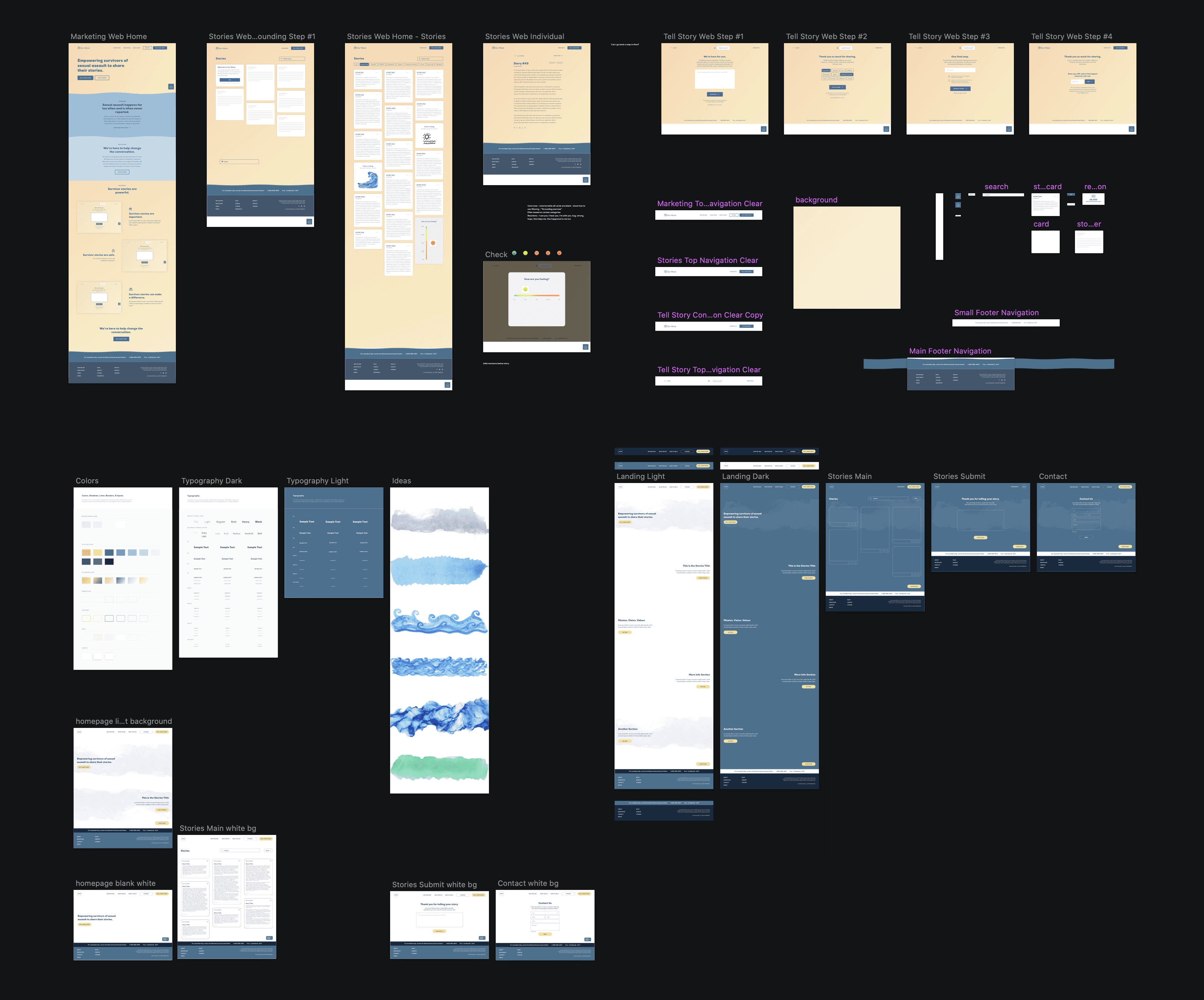

Designing the Experience

We focused on three core parts of the product:

Landing page

Story submission

Reading and supporting stories

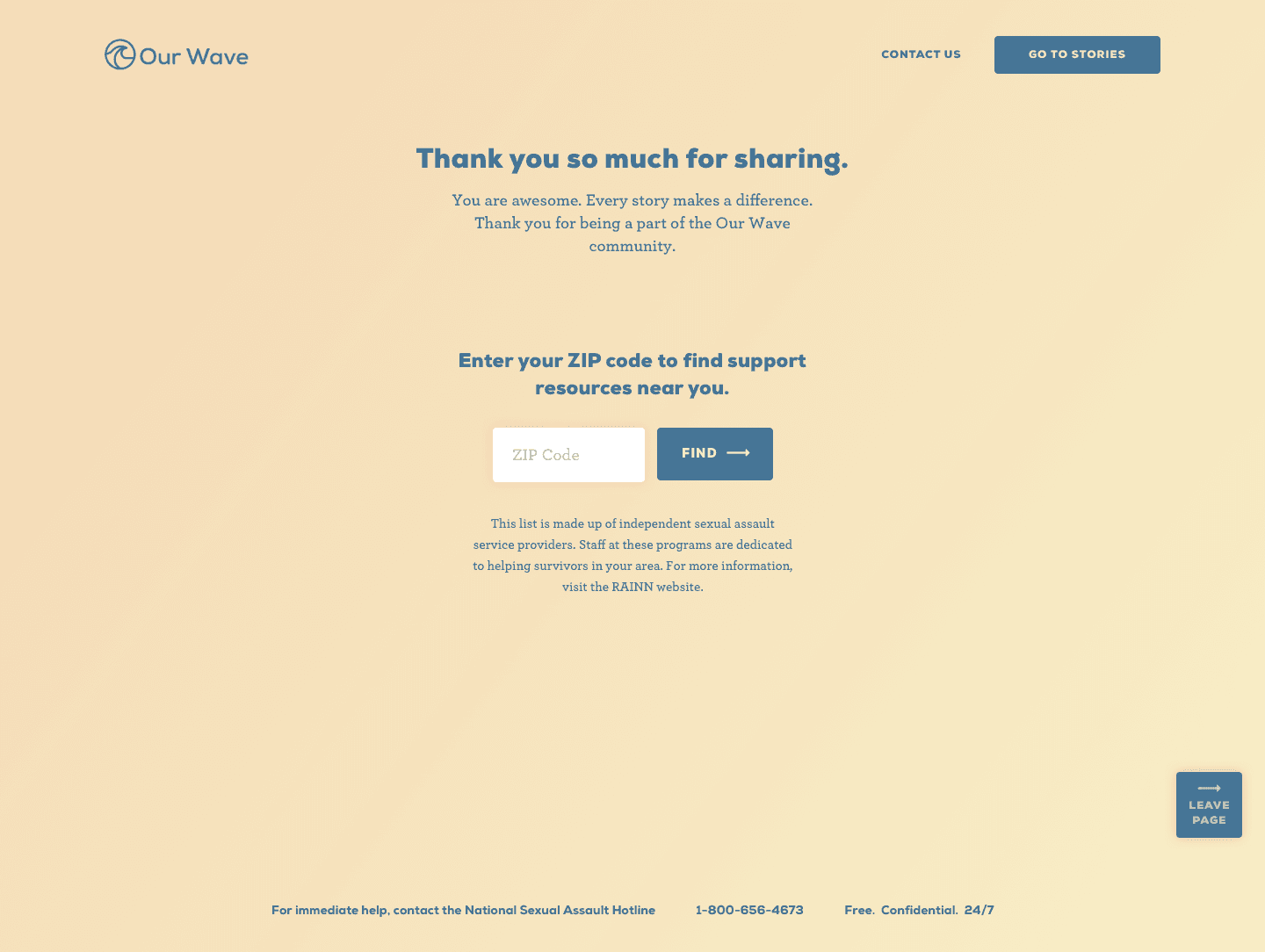

Landing page: trust and safety up front

Goals:

Clearly explain what Our Wave is.

Invite survivors to share or just read.

Make safety tools obvious.

Key decisions:

Primary CTA: “Tell your story.”

Secondary CTA: “Read stories” for people not ready to share.

Plain-language sections on: how stories are used, anonymity, and data handling.

Persistent safety tools:

A “Leave page” button that instantly redirects to an innocuous site for people browsing in unsafe environments.

National Sexual Assault Hotline displayed at all times.

The page needed to answer “Is this safe?” before “Is this interesting?”

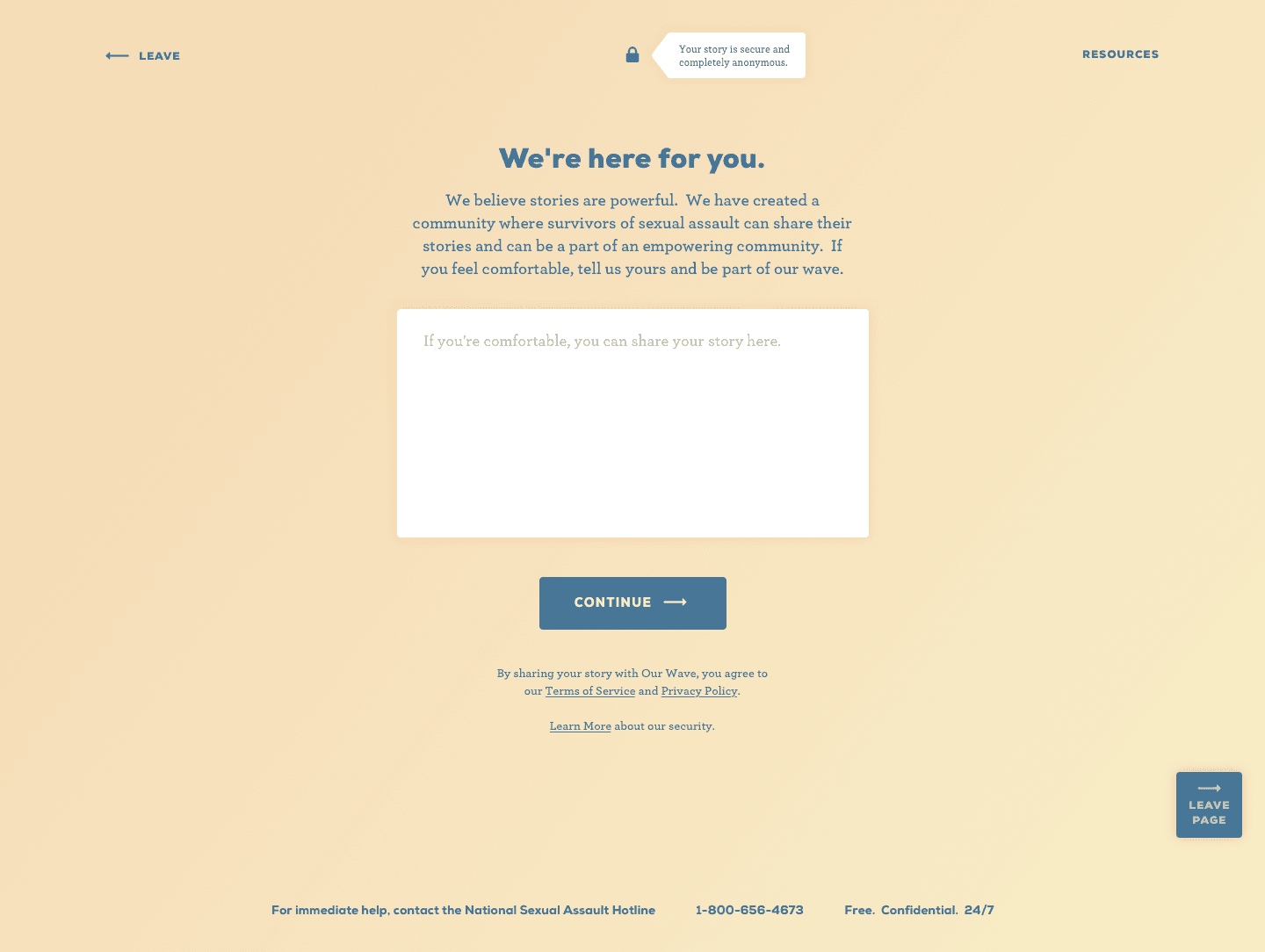

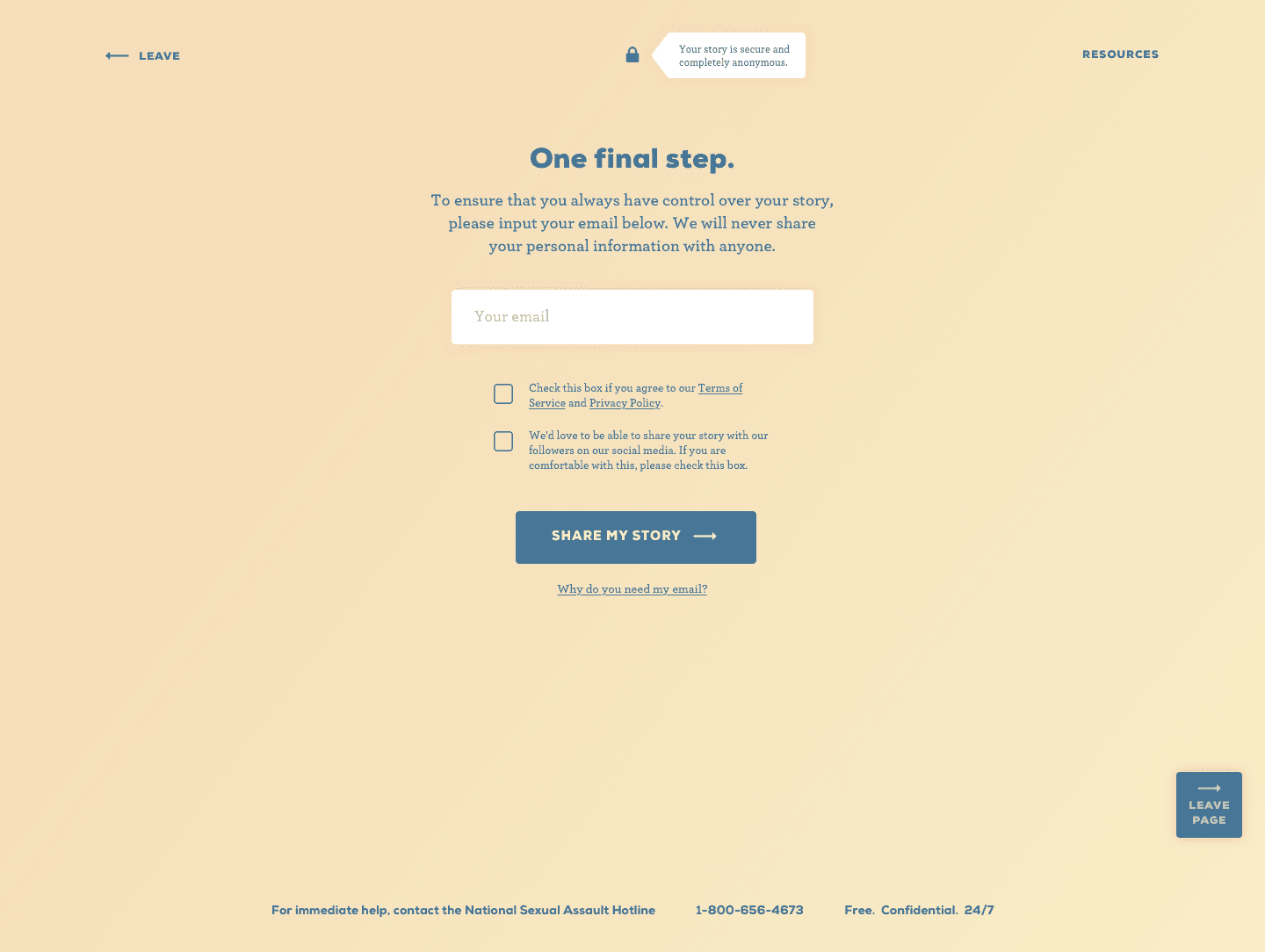

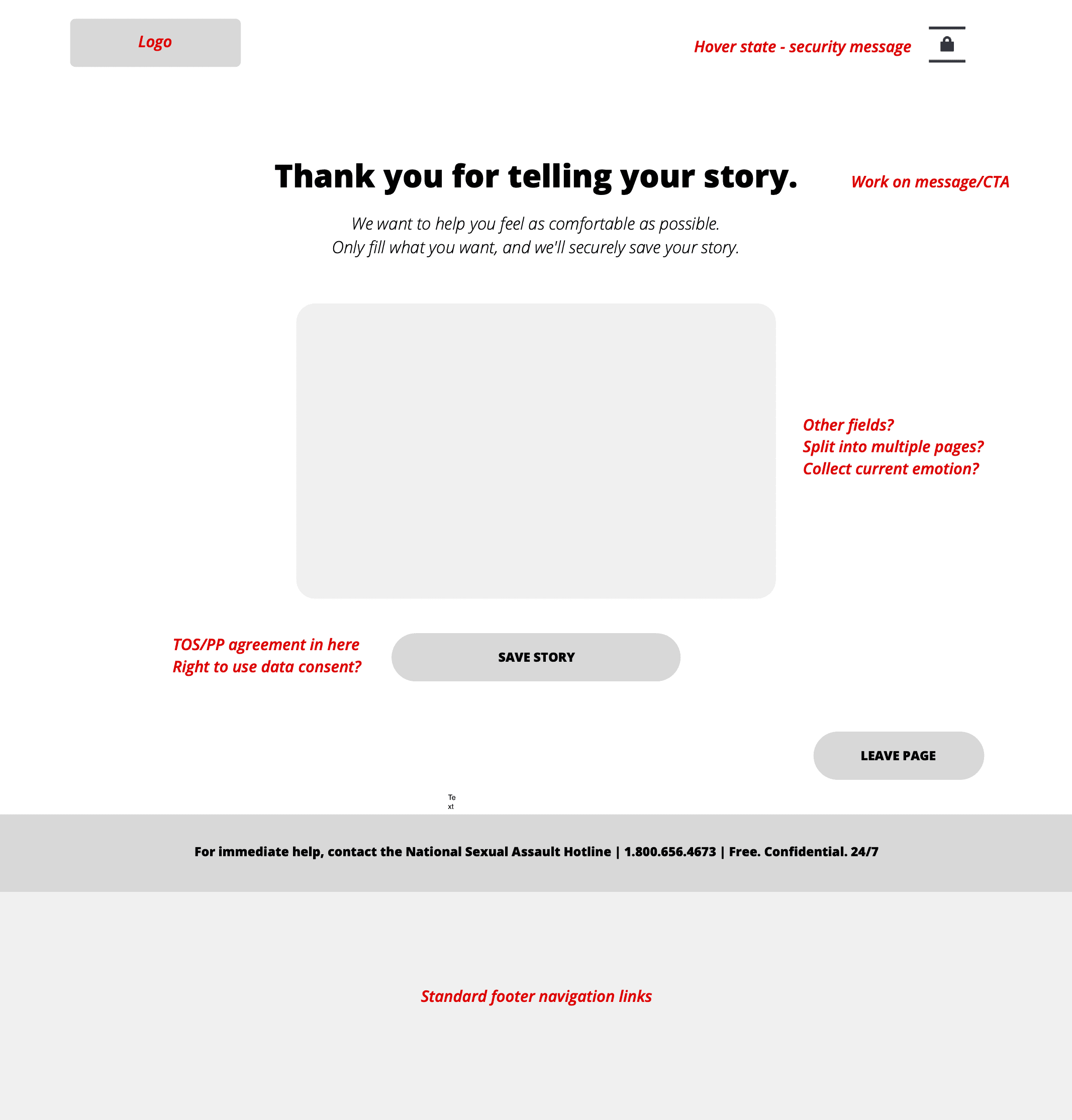

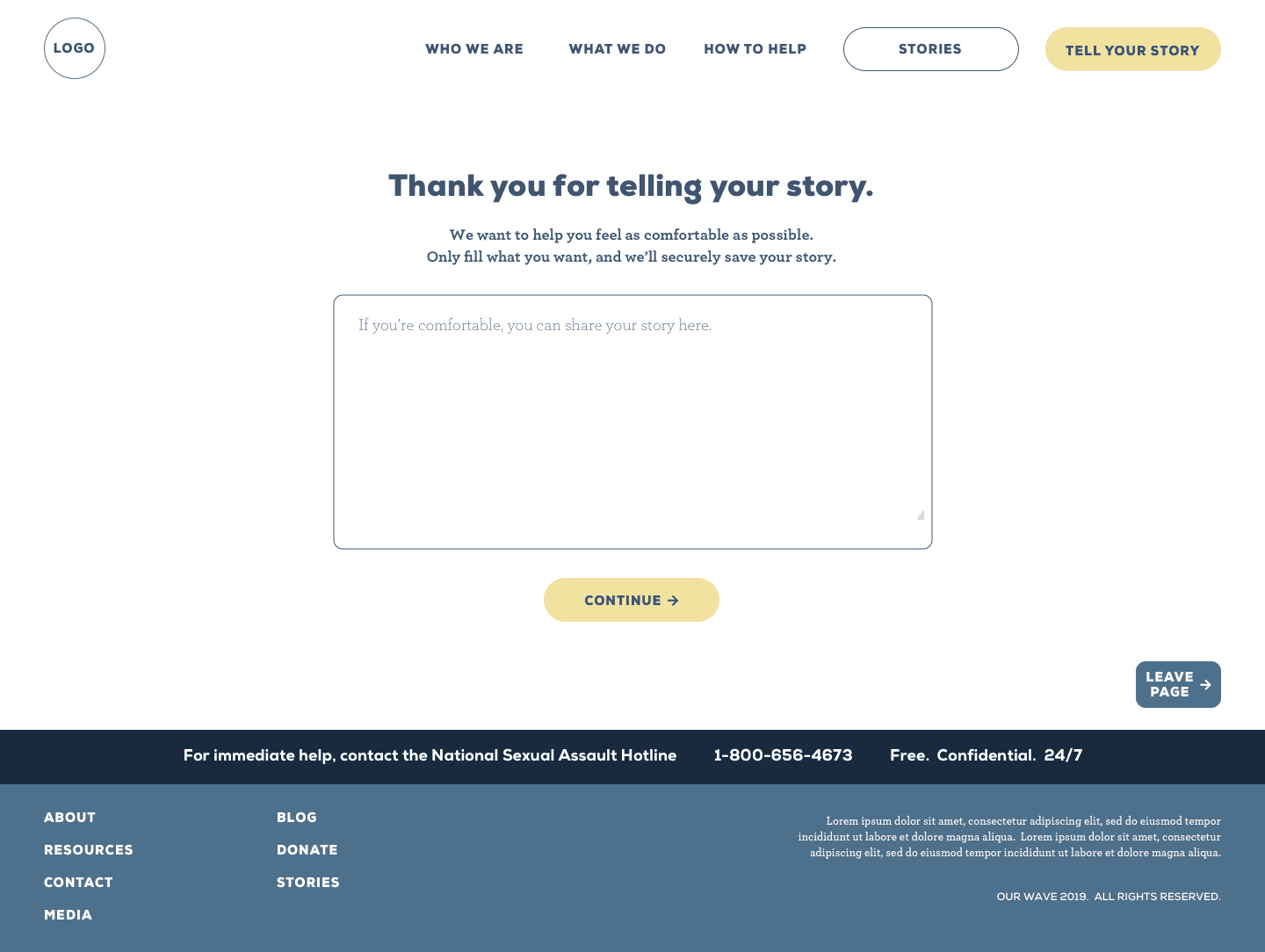

Story submission: low friction, low pressure

Design choices to reduce emotional and cognitive load:

No standard header nav

Fewer ways to accidentally leave the page; clearer focus on writing.Minimal required fields

We centered on the story text and made extra context optional. No personally identifying info was required.Trauma-informed language

Emphasized control: “Share only what you’re comfortable sharing.”

Avoided blame, diagnostic language, or sensational wording.

Clarified that stories could be completely anonymous.

Gentle guidance

Helper text for people who wanted prompts, no character counts or gamification.

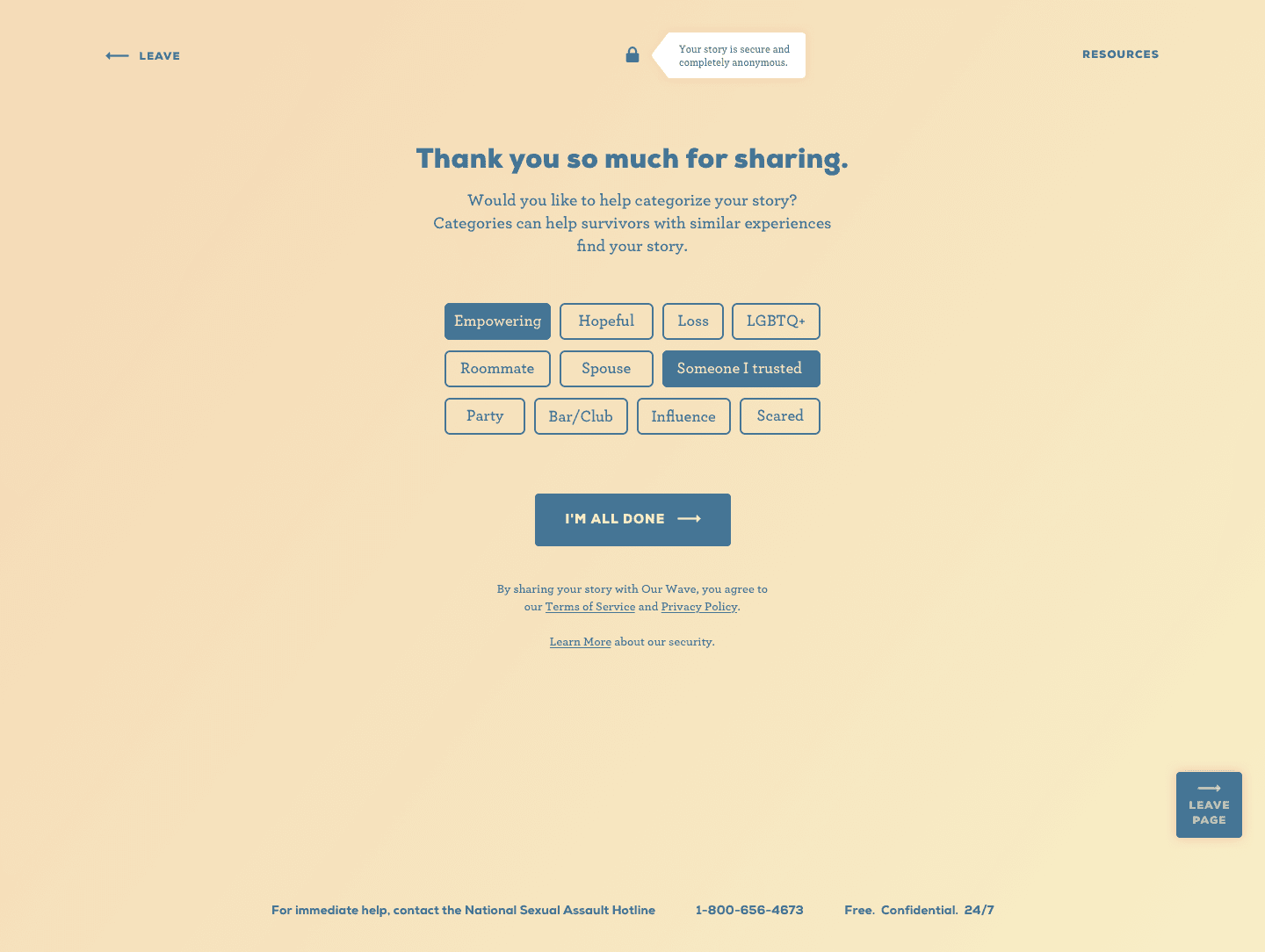

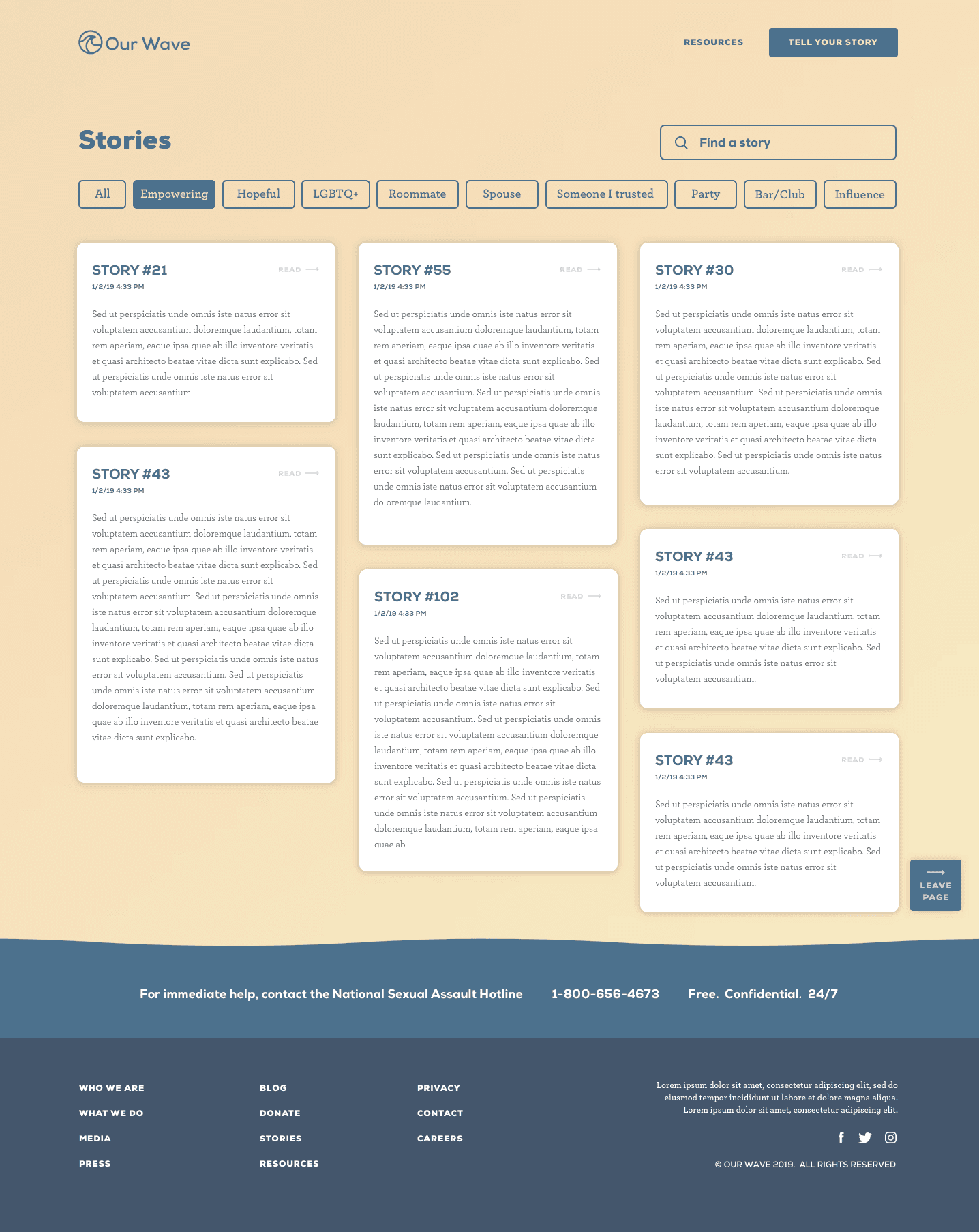

Reading stories: connection without exposure

We wanted survivors to feel less alone without turning stories into content to consume or rank.

Key decisions:

Excerpts on the main page

Let people scan for relevance and emotional readiness before clicking into full stories.Supportive reactions, not scores

Allowed simple acknowledgments like “I believe you” and “You’re not alone” instead of likes or upvotes.Careful tagging

We explored tags to help people find relevant stories, while avoiding combinations that might identify individuals (e.g., specific times, places, or institutions). Terms flagged as potentially triggering were avoided or softened.

Early studies with legal professionals.

Tested navigation, case-building tools, and data tables.

Iteration and Refinement

I led low- and mid-fidelity prototyping in Sketch and Figma, then clickable flows in InVision/Figma for review with:

Internal team

Clinicians and advocates

Selected survivors willing to give feedback

Post-launch, we used tools like Hotjar to watch navigation patterns and drop-offs. This led to:

A more prominent “Leave page” button

A simpler story form with clearer indications of what’s optional

Refined copy explaining what happens after you submit a story

Small visual tweaks to balance calm tone with accessibility

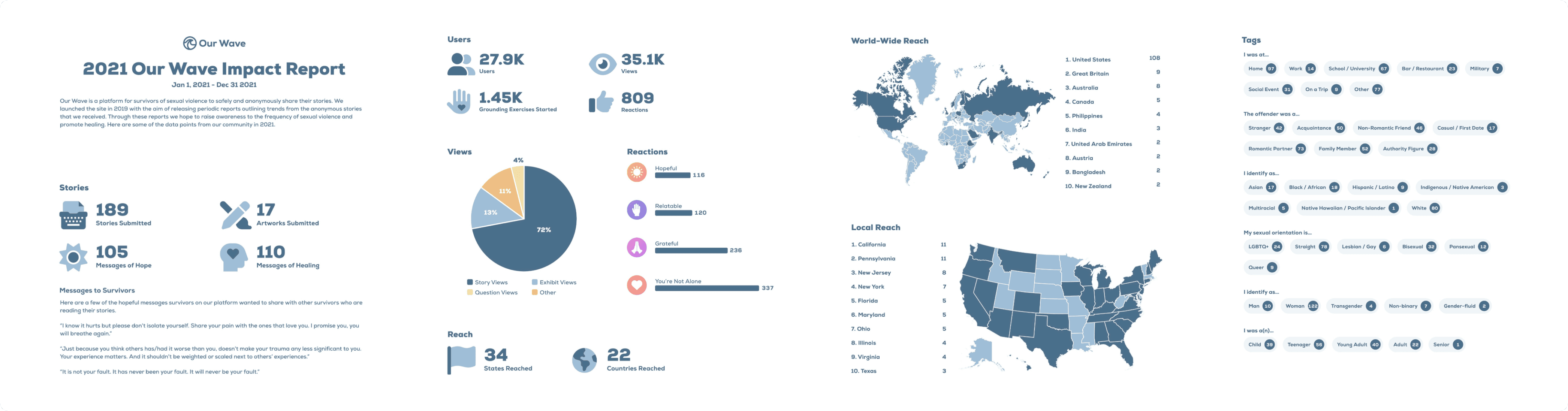

Impact

Since launch, Our Wave has grown into a global platform:

460,000+ community members

1,700+ stories from survivors in 30+ countries

1M+ story views

110,000+ resource referrals

The platform has partnered with survivor-focused organizations including:

me too. Movement

Unapologetically Surviving

End Rape on Campus

The Body: A Home for Love

It’s On Us

What I Learned

Working on Our Wave shaped how I approach sensitive, high-risk problems:

Safety and care are features, not constraints. Quick-exit controls, crisis resources, and strict anonymity policies are as important as any UI element.

Trauma-informed design requires humility and collaboration. Partnering with clinicians, advocates, and survivors was essential; this is not a space for assumptions or “move fast” experimentation.

Evidence and empathy work best together. Combining academic research, expert insight, and lived experience gave us a grounded, human-centered foundation to design from.

Ultimately, Our Wave shows how thoughtful design can help survivors feel seen, believed, and less alone—on their own terms and in their own words.

References

Cordova, Cunningham, Carlson, & Andrykowski. (2001). Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: A controlled comparison study. Health Psychology, 20, 176–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frazier, Tashiro, Berman, Steger, & Long. Correlates of levels and patterns of positive life change following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rosenthal, M. Z., Hall, M. L., Palm, K. M., Batten, S. V., & Follette, V. M. (2005). Chronic avoidance helps explain the relationship between severity of childhood sexual abuse and psychological distress in adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 14(4), 25–41. [ResearchGate]

Whiffen, V. E., & MacIntosh, H. B. (2005). Mediators of the link between childhood sexual abuse and emotional distress. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 6(1), 24–39. [PubMed]

Draucker, Martsolf, Ross, Cook, Stidham, & Mweemba. (2009). The essence of healing from sexual violence: a qualitative metasynthesis. Research in Nursing & Health, 32, 366–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O’Leary, Alday, & Ickovics. (1998). Models of life change and posttraumatic growth. In Tedeschi, Park, & Calhoun (Eds.), The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology. Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis (pp. 127–151). [Google Scholar]

Schaefer & Moos. (1998). The context for posttraumatic growth: Life crises, individual and social resources, and coping. In Tedeschi, Park, & Calhoun (Eds.), The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology. Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis (pp. 99–125). [Google Scholar]